When Writing Isn't Fantasy

- Dysgraphia Life

- Oct 11, 2022

- 8 min read

By E. L. Lyons

My head has always been in the clouds. I’m a daydreamer, a wonderer, and a wanderer. The number of times I heard my name over department store loudspeakers or had a teacher snap their fingers in my face as I stared off into nowhere when I was a kid are too many to count. When your mind is in a fantasy world, sometimes this world fades into a haze.

Who’s to blame? My dad. Absolutely his fault. He read me Tolkien and Dune as bedtime stories before I could even read Dr. Seuss.

Therein started the epic struggle of my life—a profound love for stories and an utter failure to grasp reading, writing, or paying attention. But where there’s a will, there’s a way.

I’m 31 years old, diagnosed with dysgraphia and ADHD, and have just published a 493-page epic fantasy novel.

My first obstacle, and the first I overcame, was reading. I desperately wanted to read the fantastic books that my dad had read to me, but I struggled even with the paltry slivers that I was given in early elementary school. Letters seemed abstract and I struggled to pace my eyes as I scanned the page. My eyes and mind always seemed to skip ahead or around or back. Trying to grasp the full word was difficult, and a full sentence took even more effort. My mind often wandered and I’d forget I was reading at all.

Here enters the solution: again, my dad. I can still recall him sitting me down in the living room and asking me to read aloud. At first I struggled and stumbled, and then it got marginally easier. Having that active component in the comfort of my own home changed reading for me. Over time he asked me to start narrating with “voice” and to pause at the commas and exclaim at the exclamations. He had me imitate accents of posh and rough characters. Soon, just like when he was reading to me at home, I could imagine the stories just as well when I was reading them to myself. The caveat being that I still have not mastered silently reading. I can do it; it just requires more effort. But it wasn’t long before I was reading above my grade level and with an appetite for books that rivals my appetite for pie.

During my struggle to learn to read (and lasting long after it) was the greater struggle, writing. I don’t think there are words to describe what I felt when a girl in the second grade handed her paper to me to pass to the front. I held her paper in my right hand and mine in my left for a moment, and it was all I could do to hold the tears in until I got home that night. I still get teary just remembering. There was shame, frustration, humiliation, and a sense that no matter how hard I tried, I would never be able to write something beautiful. Here was this girl, my peer, who could scratch out something that looked like calligraphy with no effort, no pain, no erasing, no scribbling out words, while I labored over just making the letters recognizable.

And there was pain, real physical pain, when I wrote. The effort it took to grip the pencil and control it, especially for long periods, left my wrist and hand sore. I assumed that everyone experienced that. I thought it was normal.

If it had just been this one event, it might not have been so clearly highlighted in my memory, but this event was preceded and followed by many.

Teachers were constantly saying I was lazy, that I was rushing, that I didn’t take my time—even when I was the last to turn in my papers, even when I was laboring over letter formation with every fiber of focus I had.

I can even recall one teacher in middle school laughing at my writing as he looked over my shoulder, that it “wasn’t what he expected when he saw me” in front of the whole class. I heard later that he joked about “the sweet, quiet girl in a pretty dress who had the handwriting of a troll” to another class. I grew up in a small town, everyone knew he was talking about me. I’m sure he didn’t intend it to be mean. He’d taught my older brother before me, and my brother had been one of his favorite students. I’d met him a good handful of times before I was in his class and he was always kind—and often making jokes. All the same, having to force an embarrassed smile when someone you respect jokes about your near-decade-long struggle to write is a memory that sticks.

But what sticks out the most to me in my struggle was my mother.

My mother tried so hard to help. She worked 60-hour weeks at times and still came home and tried to help me with my homework and my handwriting every single day. She saw how much I struggled, saw how my inability to write legibly was a stark contrast to my intelligence, and had no idea what to do, but still did everything she could to try and help me learn.

She’d make copies of my homework worksheets and have me redo them until they were legible. She’d sit with me and practice my handwriting or my spelling words late into the night, and often until two or three in the morning. Sometimes she’d tell me that I should be a writer or a journalist, but I dismissed it as the placations of a mother who loved me too much to see my flaws.

Being a writer of any sort was never an idea I entertained. In the same way that most don’t entertain the idea of becoming dragons, being a writer was simply an unrealistic, childish dream for someone like me.

And even at my most childish, I chose to dream of less painful dreams like being an artist or a musician.

But all this time, from perhaps age seven and up, I was writing stories. Notebooks and notebooks full of illegible stories were written and thrown in the trash. Once I showed one to a friend. After a few moments, she said she couldn’t read it and handed it back. I didn’t show my writing to anyone after that for a very long time. I stopped writing altogether for maybe a week—but nothing could ever keep me from a story for long. I write compulsively and with the hyperfocus of someone whose life depends on it. I didn’t write stories because I had some unrealistic dream of becoming an author. Being an author never even crossed my mind—I could barely write one page legibly and no one would ever take it seriously because it looked like a five-year-old wrote it. No, I wrote stories because I didn’t have the willpower to stop writing. Even when it negatively impacted my life (and it often did), I just kept writing. There was no goal, no dream, and no hope that spurred my writing. It was an impulse as natural and demanding as breathing. I cannot force myself to hold my breath indefinitely, nor can I force myself to hold my stories indefinitely. A certain point comes where I have to write the story.

In high school, my reading comprehension was good enough to get me into an Advanced Placement English class. A teacher there noticed my handwriting within the first week of class and pulled me aside to ask if I had dysgraphia. I had never even heard of it. That teacher advocated for me to get tested, which was no easy feat as my grades were good. As it turns out, other teachers had mentioned suspicions of dysgraphia to administrators before and been told I didn’t “qualify for testing” because of my grades. My parents and I were never informed, but I was told when I went to visit some teachers a few years after my diagnosis.

This teacher, however, was not so easily dismissed. She fought tooth and nail, and… she won. I got extensive testing and was diagnosed with dysgraphia and ADHD.

I won’t bore you with the battle for accommodations or any of the boring details. After diagnosis I continued to try and improve my handwriting, even developing a special script that aided with my print legibility. However, I got a laptop when I was seventeen, and my story-writing habit ran out of control and has continued to run ever since.

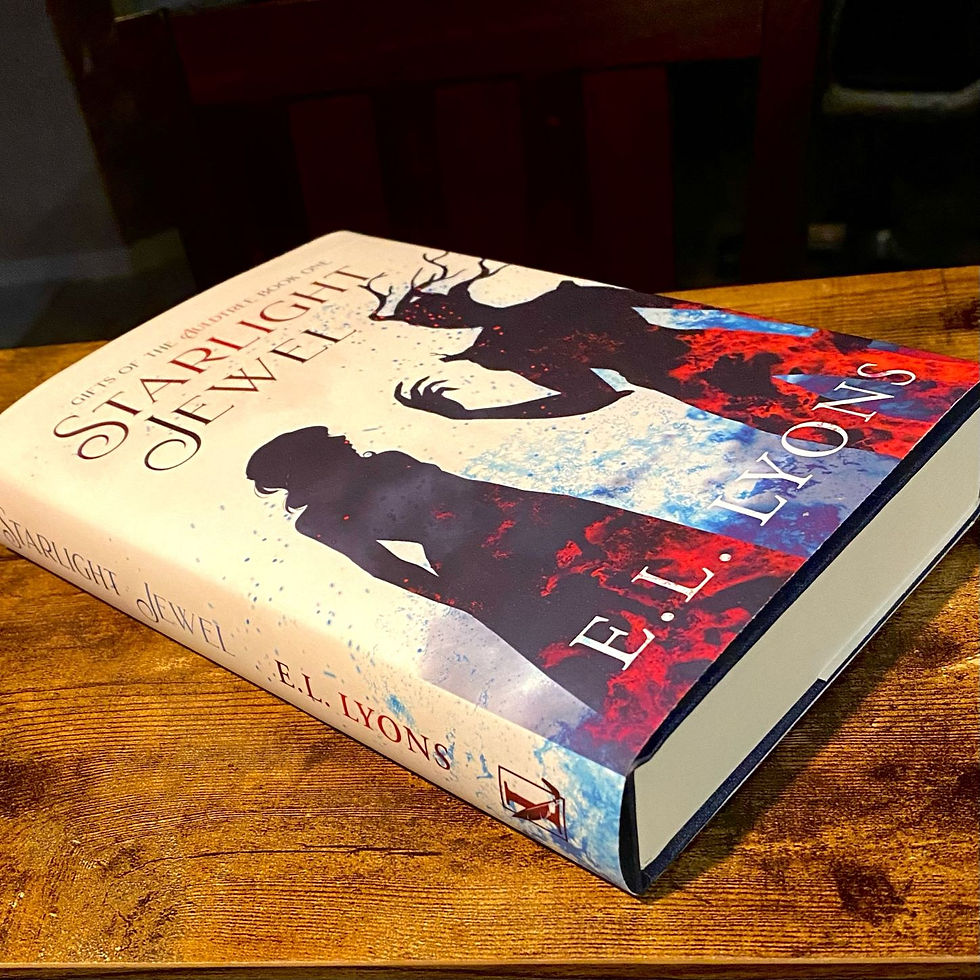

Sometime in 2020, I finished a first draft of an epic fantasy novel, Starlight Jewel. It was quite wonderful in my mind, and quite terrible when I reread it. Now, to be clear, I still had no aspirations of becoming a published author. But there’s a certain irritation that comes from doing this one thing every single day for around 25 years and still feeling like it’s just coming out terrible and not knowing how to fix it. I wanted to reread what I wrote and not cringe. One small mental meltdown and some hard advice from a friend later and I had joined a critique group.

Putting my book in front of other people that first time was in no way exciting.

In fact, it brought back all those self-conscious and painful feelings that haunted my childhood but had stayed shut away in adulthood. My fears: people would say they loved it and there would be no way I could believe that kind of nonsense; people would say they hated it and we’d all just be in agreement that I was awful. I found myself feeling guilty that people might even waste their time on it. But people did waste their time on it. And one person in particular wasted a year and a half of time on it. He read and critiqued the entire book no less than four times but probably closer to eight for some sections. All for free. He could see the bones of my story and what I was doing wrong and what I was doing right. He helped me to develop my voice and style, and to make the book exactly what I was imagining in my mind. He wasn’t the only person to waste time on my book; in fact, a lot of people have wasted time on my book. Even stranger, people have enjoyed wasting time on my book. And about halfway into 2021, I even enjoyed my reread of my book. They encouraged me to publish, and I did on September 13th, 2022.

It has yet to be judged by the masses, but I wouldn’t have sent my mind-child out into the world if I didn’t think it would hold up to scrutiny. I’ve been asked a few times how I feel now that I’ve published a book. I’ve answered with the cursory, “very excited” and a pleasant smile, but that doesn’t really begin to cover what I feel. I feel blessed. One thing I didn’t mention about my dad, who was the cause and the cure for all my reading and writing woes, is that he too had dysgraphia that went undiagnosed. And he also had a love for reading and writing. But he didn’t live in an age where computers were everywhere, and he didn’t have the support I had growing up, and he didn’t have an explanation for his troubles until well into adulthood. What could he have written if he’d had my life? I feel blessed to live in a time where we not only recognize dysgraphia, but there are computers to help us overcome some of the larger obstacles with it.

How do I feel about publishing a book? Like I achieved a dream that I was too scared to let myself hope for.

Starlight Jewel is available now. (Note: Dysgraphia Life is an Amazon affiliate and receives a percentage of purchases through our links, at no cost to you.)

Comments